Exeter

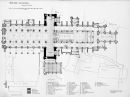

Exeter became the seat of a bishop in 1050 when the then two separate sees of Cornwall and Devon were united under Bishop Leofric. King Edward the Confessor and his Queen attended Leofric’s installation and the foundation charter recording the event is in the cathedral library. Previously the see had been located at Crediton but there had been a monastery at Exeter intermittently since the 7th century, most recently rebuilt in 1018. The original Saxon cathedral sufficed for a while after the Conquest, but a new Norman building was begun in 1112 by Bishop William Warelwast (a nephew of William the Conqueror): the east end and first two bays of the nave were consecrated in 1133, and the rest of the nave was finished around 1150. The only major items remaining today of this building are the unique twin towers (located over each of the transepts) – the north tower known as St. Paul and the south as St. John from the chapels in them.

The rest of the cathedral is the result of the work of a succession of very active bishops who, in just over 100 years, transformed the building from Norman to Decorated Gothic -- the results of their labors are pretty much what we see today, though alterations and enhancements continued through to the end of the 15th century. The most important of these bishops were Bishop Branscombe, who set the whole process in motion, and Bishops Stapledon and Grandisson who completed it. Building proceeded in phases, interrupted by the Black Death: first the east end and east nave, then the rest of the nave and west front, finally the cloisters and west-front sculptures.

Rebuilding began in 1275 (around the year in which Salisbury cathedral was completed) and, as in the original construction, work progressed from east to west – for a long time the cathedral was divided into two so that construction work could progress in the east end while services continued in the nave. The new quire and presbytery were consecrated in 1328, by which time the Lady Chapel was already complete – the retrochoir between the two was completed at the end of the 13th century. As a part of the overall design of the quire, vaulted galleries were added high above the ground in the transepts for the use of choristers to deliver music from above. The stone pulpitum was completed by about 1325 and, as in several other cathedrals, it was later put to use as the platform on which to build the cathedral organ. The quire stalls were moved and replaced on several occasions: the present ones are Victorian replacements by Scott, though, miraculously, the original misericords survive, dating from the 13th century and are the earliest complete set in England.

Work on the nave began in the early 1320’s, partially making use of the original Norman walls, with a great variety of elegant tracery in the windows, and was completed around 1360 (with an interruption for the Black Death). Purbeck marble was used for the pillars in the nave, but at Exeter it wasn’t polished to a glossy black as in other cathedrals, but to a much more subtle bluish-grey color. Although located in a red sandstone area, Exeter primarily used a somewhat harder cream sandstone from Beer for its construction, so that it didn’t suffer as much from the depravations of the elements as the red sandstone cathedrals. Exeter’s nave is relatively long and wide, rather than narrow and high, and this perspective is enhanced by the original radical use of only two levels in the nave, an arcade and clerestory, omitting the triforium -- though a small one was inserted when the choir was re-built and was extended into the nave for continuity, but this didn’t change the overall height of the nave. Following the work on the nave, the major building effort focused on the west front and its magnificent array of medieval sculptures, started in the 1350s and not completed until the 15th century.

Exeter is unique among English cathedrals in not having a central tower and the associated massive piers to support it in the nave. As a result that there is no prominence at the crossing as such and the magnificent Gothic ribbed vault (completed around 1350) runs the full length of the cathedral for over 300 feet, forming the longest unbroken stretch of Gothic vaulting in the world, studded with a magnificent set of carved bosses. Together with the Purbeck marble pillars, rich moldings and carvings, the interior is one of the most glorious creations of Decorated architecture anywhere, evenly balanced as it is between the almost equal size of the nave and quire. In spite of its moderate scale as compared with some other cathedrals, this gives a great impression of spaciousness.

Exeter didn’t suffer too much at the Dissolution as it wasn’t a monastery, but more serious damage was done during the Civil War when the cloisters were destroyed. Following the Restoration, in 1645 a new pipe organ was built on the pulpitum by John Loosemore -- a very impressive instrument. There was some interior restoration by Scott in the 19th century, but nothing too dramatic. In 1942 St James’s chapel and the south side of the quire were hit by a bomb causing significant damage – this was repaired in the 1950s.

The rest of the cathedral is the result of the work of a succession of very active bishops who, in just over 100 years, transformed the building from Norman to Decorated Gothic -- the results of their labors are pretty much what we see today, though alterations and enhancements continued through to the end of the 15th century. The most important of these bishops were Bishop Branscombe, who set the whole process in motion, and Bishops Stapledon and Grandisson who completed it. Building proceeded in phases, interrupted by the Black Death: first the east end and east nave, then the rest of the nave and west front, finally the cloisters and west-front sculptures.

Rebuilding began in 1275 (around the year in which Salisbury cathedral was completed) and, as in the original construction, work progressed from east to west – for a long time the cathedral was divided into two so that construction work could progress in the east end while services continued in the nave. The new quire and presbytery were consecrated in 1328, by which time the Lady Chapel was already complete – the retrochoir between the two was completed at the end of the 13th century. As a part of the overall design of the quire, vaulted galleries were added high above the ground in the transepts for the use of choristers to deliver music from above. The stone pulpitum was completed by about 1325 and, as in several other cathedrals, it was later put to use as the platform on which to build the cathedral organ. The quire stalls were moved and replaced on several occasions: the present ones are Victorian replacements by Scott, though, miraculously, the original misericords survive, dating from the 13th century and are the earliest complete set in England.

Work on the nave began in the early 1320’s, partially making use of the original Norman walls, with a great variety of elegant tracery in the windows, and was completed around 1360 (with an interruption for the Black Death). Purbeck marble was used for the pillars in the nave, but at Exeter it wasn’t polished to a glossy black as in other cathedrals, but to a much more subtle bluish-grey color. Although located in a red sandstone area, Exeter primarily used a somewhat harder cream sandstone from Beer for its construction, so that it didn’t suffer as much from the depravations of the elements as the red sandstone cathedrals. Exeter’s nave is relatively long and wide, rather than narrow and high, and this perspective is enhanced by the original radical use of only two levels in the nave, an arcade and clerestory, omitting the triforium -- though a small one was inserted when the choir was re-built and was extended into the nave for continuity, but this didn’t change the overall height of the nave. Following the work on the nave, the major building effort focused on the west front and its magnificent array of medieval sculptures, started in the 1350s and not completed until the 15th century.

Exeter is unique among English cathedrals in not having a central tower and the associated massive piers to support it in the nave. As a result that there is no prominence at the crossing as such and the magnificent Gothic ribbed vault (completed around 1350) runs the full length of the cathedral for over 300 feet, forming the longest unbroken stretch of Gothic vaulting in the world, studded with a magnificent set of carved bosses. Together with the Purbeck marble pillars, rich moldings and carvings, the interior is one of the most glorious creations of Decorated architecture anywhere, evenly balanced as it is between the almost equal size of the nave and quire. In spite of its moderate scale as compared with some other cathedrals, this gives a great impression of spaciousness.

Exeter didn’t suffer too much at the Dissolution as it wasn’t a monastery, but more serious damage was done during the Civil War when the cloisters were destroyed. Following the Restoration, in 1645 a new pipe organ was built on the pulpitum by John Loosemore -- a very impressive instrument. There was some interior restoration by Scott in the 19th century, but nothing too dramatic. In 1942 St James’s chapel and the south side of the quire were hit by a bomb causing significant damage – this was repaired in the 1950s.